During our summer research camp, and as part of our “Historical Humanities” team, I began scanning ProQuest databases and the digital collections of the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America project for historical newspapers and their discussion of the humanities and liberal arts during the Great Depression (1929-1939).

In looking through the historical news accounts featuring humanities and liberal arts, I was led by two main questions: What value did commentators, journalists, politicians, and educators claim an education in the humanities and liberal arts to have? What was the significance of the crisis moment in which this happened—in other words, what was the impact of the Great Depression and America’s looming beginning involvement in World War II on the discussion of the humanities and a liberal arts education?

After a first exploratory search of the New York Times, Chicago Daily Tribune, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and the Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), it appears that from the late 1920s through the 1930s, the humanities and liberal arts were discussed in overwhelmingly favorable terms in the American press. In newspapers during the Great Depression, arguments presented for the significance of a college education, and specifically a liberal arts and humanities training, could be grouped around two main themes:

Firstly, on a practical level, the age of employment of young people had to be deferred because of the dire economic conditions. Unable to join the workforce immediately after high school, American youth had to be kept busy in other ways. Interestingly, a college education was thus used as a method to alleviate the effects of unemployment and essentially keep young Americans off the streets in the interest of preserving social order and safety. As Dr Harry Woodburn Chaso, chancellor of NY University, explained in a 1935 article in the Chicago Daily Tribune:

“We are confronted by the necessity of caring for the education of more and more young people up to the age of maturity. It is not socially safe in a democracy to leave young people without opportunities for education.”[1]

The latter part of his argument might have been informed by the concern that a lack of education coupled with little to no job opportunities could potentially drive individuals into the arms of “undemocratic” groups (be it Communists or Fascists) gathering members among the unemployed. This perception of the benefits of a college education was still shared in 1937 by an Iowa educator, who was quoted in the Los Angeles Times saying that “since the depression young men and women find it harder to get work and thus are more apt to have time for a well rounded education, cultural as well as technical.”[2]

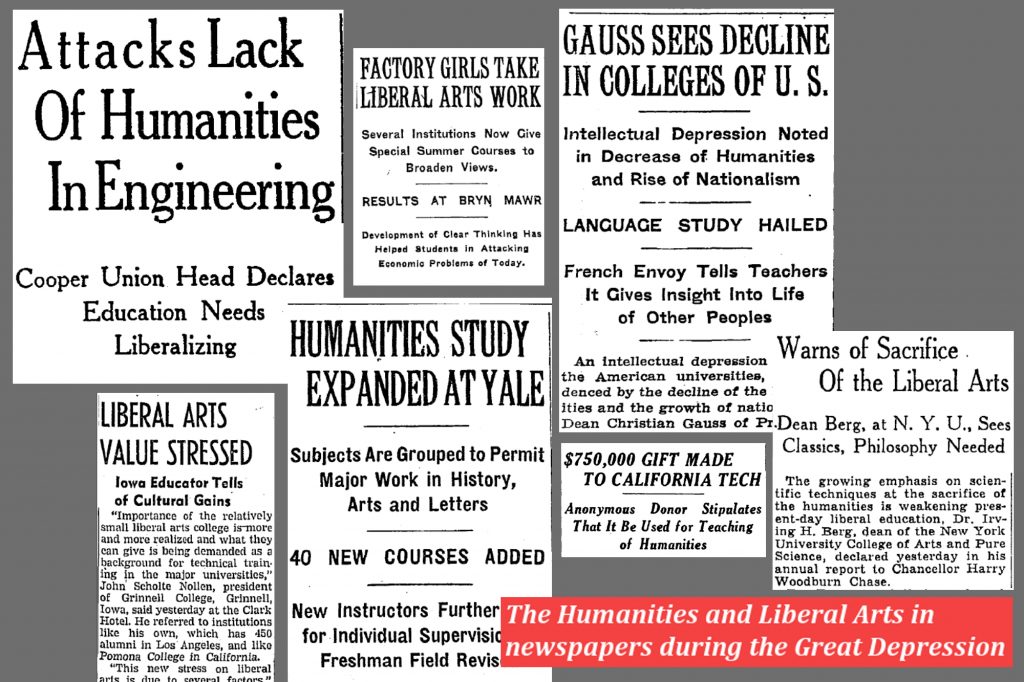

Overall, an education in the liberal arts and humanities was not seen as opposed to industrial employment and technical training, but as a necessary part of a balanced education for individuals in various industries and trades. Even factory girls were given the opportunity to take summer courses in the liberal arts at several institutions of higher education, a project that had been introduced at Bryn Mawr, a private college in Pennsylvania, in the early 1920s. The two month summer school was not meant to lead to a better job for its participants, and no exams or credentials were given. Rather, the aim of these programs was to “promote clear thinking and to stimulate an interest in the problems of our economic order,” equipping its students with the necessary skills to take part in the solution of problems of industrial workers.[3]

Secondly, then, beyond keeping American youth busy, an education in the humanities and liberal arts was also expected to play a part in the making of minds that would help improve and advance American society under the pressure of the Great Depression and in the spirit of the New Deal. Educators called for a better integration of the humanities in the engineering curriculum of colleges. For example, Dr Burdell, head of Cooper Union, a privately run college in Lower Manhattan, complained in 1930 that many engineering graduates were inept at applying their engineering knowledge to actual social circumstances and unprepared to succeed in climbing the career ladder. Perhaps more importantly, Dr Burdell was concerned about the eventual consequences of an education lacking in the humanities and liberal arts beyond the students’ career prospects:

“Reason tells us that young men little schooled in history, and in the basic principles of human behavior, and with views on racial, economic, and political matters that are a composite of personal prejudice and current propaganda, are ill fitted to step into positions of leadership, where calm judgment, understanding and broadmindedness are required. I firmly believe that an integrated study of the social sciences and the humanities will leave our engineering students less susceptible to the prevailing shibboleths, clichés and slogans regarding race, creeds and political programs. Stereotyped thinking is swifter and less painful, but is is far more dangerous in these days when adaptability is necessary for survival.”[4]

Similarly, an article in the Washington, D.C. paper Sunday Star from 1934 critically compared the political and social developments in Russia, Germany, and Italy with those in the United States, stating that unlike the other three nations, the United States was founded on the belief in the liberty of the individual, which the state serves, rather than the other way around. Lloyd Morris argued that such individual liberty would be impossible without the freedom to choose your own work and career, which in turn he saw based in a college education with a focus the humanities; an education that should do much more than just prepare adolescents to earn their livelihood. While Morris admitted that “the old humanities” might never help raise anyone’s paycheck, his article presented them as indispensable because they “open many doors upon a more abundant life,” and Morris called for an expansion of the obligatory service of education.[5]

Accordingly, a possible decline of a humanities and liberal arts education was regarded as dangerous to a functioning democracy. In 1938, Princeton University dean Christian Gauss warned about the intellectual depression brought on by diminishing language instruction in the United States, a trend that in its worst iteration would lead to heightened nationalism – not a nationalism that was traditionally American, but a nationalism of the kind of the Ku Klux Klan, one that attacked the freedom of speech and civil liberties. Instruction in foreign languages, Gauss believed, was one crucial countermeasure to such superpatriotic, undemocratic tendencies in the name of “Americanism.”[6]

It is perhaps not surprising, then, to find in the historical newspapers the trend of a “liberalization” of the college curriculum during the 1930s, even at technical universities, and an investment of private donors into humanities programs. I found numerous articles reporting on grants given to scholars in the humanities, and donations to Universities in the interest of expanding education in the liberal arts. In 1930, for example, the Rockefeller Foundation awarded $90.000 to the American Council of Learned Societies, enabling them for the first time to offer post-doctoral fellowships in the humanities.[7]In 1937, an anonymous donor gifted $750,000 to California Tech, under the stipulation that the money would be used to balance out the science-based curriculum with cultural education.[8]And in the same year, Columbia University’s president Dr Butler welcomed the expansion of the University’s humanities curriculum. A humanities survey course became prescribed to Freshmen and Sophomores, departing from what he described in a New York Timesarticle to have been a “narrow program.”[9]Similarly, Yale significantly expanded its humanities program in 1938, with sixteen new instructors joining the faculty.[10]

In conclusion, the articles I have found suggest that a humanities education was highly regarded in mainstream public discourse throughout the crisis of the Great Depression. I have not come across any articles calling for a de-funding of the humanities, or arguing against their importance. The value given to the humanities and liberal arts is found on a sliding scale ranging from practicality – American youth needed to be presented with alternatives to employment straight out of high school, and engineers were expected to only do their job right when understanding the role of their profession in society – to moral, ethical and political concerns that saw a humanities education as a bulwark of American democracy and individual freedom against domestic anti-Democratic tendencies growing in the wake of totalitarian regimes that were gaining

[1][n.a.] “Liberal Arts Colleges Are Under Fire.” Chicago Daily Tribune,27 January 27th, 1935. D3.

[2][n.a.] “LIBERAL ARTS VALUE STRESSED: Iowa Educator Tells of Cultural Gains.” Los Angeles Times,March 24th, 1937. A12.

[3]Worthington Smith, Hilda. “Factory Girls Take Liberal Arts Work: A Glimpse of Science for the Industrial Worker.”New York Times, July 5th, 1931. 39.

[4][n.a.] “Attacks Lack Of Humanities In Engineering: Cooper Union Head Declares Education Needs Liberalizing.” New York Times, November 12, 1939. 61.